Damas: A Welcoming Respite On the Aegean Shore

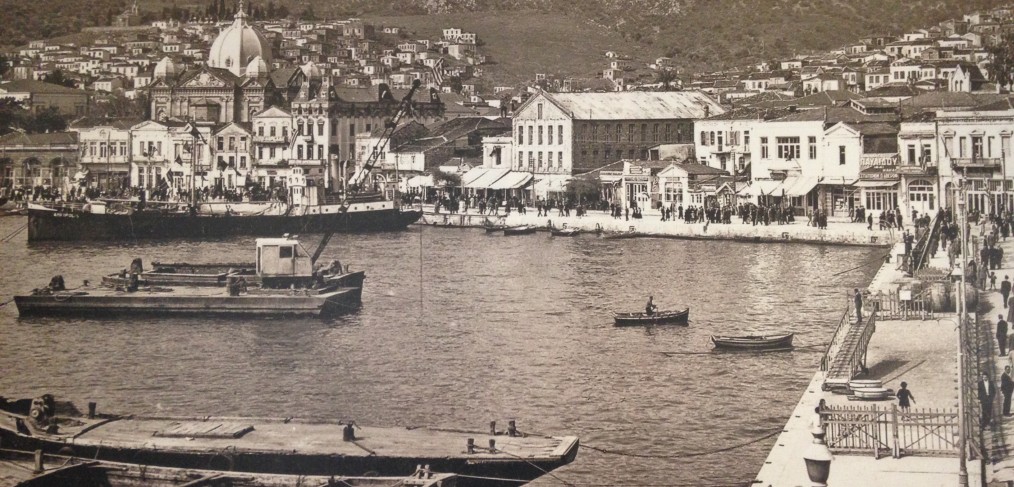

At its nearest, the shores of Turkey are a mere five kilometers away from the Greek island of Lesbos, close enough for the people of Lesbos to witness lines of boats heading towards their island. At first a trickle at the onset of the Syrian Civil War, the flow of refugees – along with other regional migrants from the surrounding nations – swelled to many boatloads, arriving everyday for the past couple of years. For the Strait of Mytilini, however, this is an old story.

Almost a century ago, in 1922, thousands of Anatolian Greeks, or Greeks that lived in what is present-day Turkey for millennia, migrated en masse to the islands of Greece. This was post-World War I regional socio-politics at its most contentious, resulting from a dictate by Kemal Ataturk to forcibly remove all Greeks from Turkish soil. The population of present-day Lesbos is largely descended from these refugees of a century ago.

Yet, there remains a stark difference between the two historic migration flows. The former was mostly of ethnic Greeks Orthodox Christians, whereas the boats arriving on the shores today are a mosaic of the Middle East – Syrian, Iraqi, Muslim, Christian, Yezidi, etc. Furthermore, most won’t call Greece, let alone Lesbos, home. The Aegean island is just one of the many stops along the migrants’ arduous journey towards a hopeful future in Northern Europe. Yet, for whatever period of time the migrants stay, their presence undeniably changes Lesbos. Tourism, which was the mainstay of the local economy, has all but vanished, further exacerbating the lingering Euro recession. Local shops and hotels have been gravely impacted by the influx of migrants on their streets and shores.

Understanding both sides of issue, Alki Thomaniku decided it was time to do something about it. Though he was concerned for the local economy, he also understood how things looked from the other side, as he himself arrived 25 years ago as a migrant from Albania. Alki partnered up with a local Lesbos resident, Mr. Vangjelis Asvestas, to open a restaurant that not only served halal Syrian food, but also offered a place for the migrants to catch their collective breath. Damas, which is Syrian colloquial for Damascus, opened its doors in October of 2015. It’s fitted with washrooms and changing areas, a corner of the restaurant serves as a prayer space, and cushions are laid out for anyone to take a much-needed slumber. Most importantly, and many times free of charge, Damas offered the refugees a taste of home.

Food remains central to any migrant’s identity. This phenomenon holds true in almost every ethnic enclave around the world. Clothing may give way to assimilatory pressures, and many times, mother tongues may become vestigial. However, the cuisine of one’s ancestors, passed down through the pots and pans of parents and grandparents, often clank through the generations. Food is visceral. Food is hearth – it is safety. As it arouses the senses of a body, from the olfactory links with nostalgia to the textural pleasure of taste, food makes us what we are. That is, living, breathing, and most importantly, feeling beings.

That savory filling in the kibbeh served as an appetizer at Damas? No, that’s not just minced meat mixed with spices. In it are also pine nuts, full of memories of hillside orchards, of childhood weekends spent in Sinjar. The smoky babaganoush reminds them of stories of baba himself, who competed with mom to make the best meze. And the first bite of shawarma quickly transports to a favorite hangout spot in the narrow alleys of Damascus itself. The menu at Damas is not just a long list of ingredients. For many, it is a return to a home that they may never see again.

Then, there is the tea. It’s as ever-flowing as the Firat itself, with the kitchen staff brewing countless vats of it everyday. And where there is tea, there is community. Groups of men and women share news and stories while sipping tea at Damas, detailing harrowing ordeals or sighing hopeful conclusions of their respective journeys. And just like any true chaikhane, Damas’s kitchen is 7-day-a-week, 24-hour-a-day institution.

Then, there is the tea. It’s as ever-flowing as the Firat itself, with the kitchen staff brewing countless vats of it everyday. And where there is tea, there is community. Groups of men and women share news and stories while sipping tea at Damas, detailing harrowing ordeals or sighing hopeful conclusions of their respective journeys. And just like any true chaikhane, Damas’s kitchen is 7-day-a-week, 24-hour-a-day institution.

So too are Alki’s phones. They are seldom silent, as he connects foreigners with local NGO’s, or help town officials gauge the next wave of migrants. Overtime, Damas became the island’s international dialogue center. Organizations and volunteers from around the world are pouring into Lesbos to help, assess, or abet the situation. Damas links these disparate groups under one roof, albeit through a very multilingual menu. Currently, the menus is in five languages – Arabic, English, Greek, Turkish, and Farsi – reflecting the complexity of the situation, with refugees and migrants pouring in from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Damas is currently working on its Mandarin language menu, responding to the needs of the large cohort of Chinese volunteers on the island. UN charters can learn a thing or two from this menu alone.

Food history and human migrations have always been intricately connected, and what’s happening now in Dama’s kitchen, and by extension, throughout the Aegean, has seen countless iterations over the past 10,000 years. The ancestors of most modern Europeans were actually Neolithic migrants who originated from the same region as today’s mass of refugees, from the same Mesopotamia and land of Fertile Crescents and ever-dwindling crosses. It was their domesticated animals and fruits, their ‘technology’ of farming, which sowed the seeds of European civilization.

Fast-forward ten thousand years later. Business is once again picking up in Lesbos, so much so that there are talks of opening up another Damas on the island to meet the increasing demand. But for Alki and his friends, the end goal will always remain the same. Damas began as an oasis for the tired and travel-weary masses, a refuge for those seeking a safer future in an unknown continent. At its core, it is a place that serves people the warmth of home. The doors of Damas and the shores of Lesbos have remained, and apparently will always remain, open.

Damas was recently featured on CNN. Click here to view the clip.

About the Author

Abdul-Kadar (AK) Rahim is a marketer and product developer with a healthy obsession with all-things culinary. He is part of NooshTube’s creative team, collaborating on content and marketing. Though brought up on the East Coast, he has a tendency to roam around the world, collecting stories and recipes along the way.

Wonderful article!