Food Sovereignty: Sustaining Cultural Identity and Self-reliance

By: Rachael Novak

If you’ve ever been to a powwow, chances are the unmistakable scent of warm fry bread and the temptation to try a “Native American food” lured you to one of the food vendors. It’s far less likely, however, that you learned much about the complex history of this powwow staple, now beloved by so many across Native America and beyond. While fry bread is undeniably delicious, it has contributed to high rates of obesity and diabetes in American Indian communities. In fact, the Federal government has distributed many processed foods that are high in calories and unhealthy fats and low in nutritional value throughout the various waves of physical and cultural displacement of Native peoples over the last 150 years. In particular, the forced movement onto reservations restricted access and connection to the land and food sources that had sustained Native Americans for time immemorial. A century and a half of historical trauma and federal policy has contributed to the prevalence of modern-day “food deserts” in too many Native American communities, equating to a dearth of access to healthy and high quality foods.

These startling facts motivated Danya Carroll, from the White Mountain Apache tribe and the Navajo Nation in Arizona, to pursue her work as a Research Program Coordinator for the Feast for the Future Program, a nutrition program at the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health. Driven by a desire to help her community, Danya and her colleagues have been implementing this program for several years on the Fort Apache Indian reservation. Danya describes the new approach this program is taking, “tribes and public health professionals are looking at different solutions for tribes- we have the answers to our own problems, it’s just an issue of getting the needed resources to the community”.

Feast for the Future is built upon the concept of food sovereignty. For Native American communities, food sovereignty represents cultural preservation through self-sustenance. Carroll defines it as, “the ability of tribes to feed themselves and provide culturally important foods for their communities in sustainable ways”. Danya’s work involves examining tribally-driven solutions and providing communities with resources tailored to their needs.

Take the example of a garden – Danya and her team create school gardens in local Apache communities to teach youth about the importance of healthy, local foods and help youth strengthen their connection with Mother Earth. Tending the garden, the youth learn about the importance of growing healthy food for self-reliance. Danya also brings in community elders to teach kids in the garden about traditional local Native foods, perpetuating cultural identity through intergenerational education. They discuss traditional practices that have sustained their peoples for many centuries: “ they learn a lot of things just through food, whether it’s hunting or gathering or growing these different foods that are important to people… those foods that their ancestors survived on. It’s really important cause it impacts a lot of areas, not just physical health but it plays a huge role in mental health- all our well-being as families and I think the overall community.” In Danya’s words, “food is pretty much the thread that keeps communities together.”

Take the example of a garden – Danya and her team create school gardens in local Apache communities to teach youth about the importance of healthy, local foods and help youth strengthen their connection with Mother Earth. Tending the garden, the youth learn about the importance of growing healthy food for self-reliance. Danya also brings in community elders to teach kids in the garden about traditional local Native foods, perpetuating cultural identity through intergenerational education. They discuss traditional practices that have sustained their peoples for many centuries: “ they learn a lot of things just through food, whether it’s hunting or gathering or growing these different foods that are important to people… those foods that their ancestors survived on. It’s really important cause it impacts a lot of areas, not just physical health but it plays a huge role in mental health- all our well-being as families and I think the overall community.” In Danya’s words, “food is pretty much the thread that keeps communities together.”

Unfortunately, the intergenerational sharing of this “thread” has been disrupted in American Indian communities for many reasons, including the prominent ones previously mentioned: the historical trauma of removal from homeland, assimilation efforts of boarding schools, and over a century of federal policies toward American Indians.

While Danya works primarily within her own communities, she can draw similarities between the disruption of cultural identity experienced by Native American communities and many immigrant communities. These ‘newer Americans’ are also often displaced by social, economic and political strife from their homelands and therefore their access to culturally important foods is also disrupted. There are lessons from this land’s first peoples that can benefit its newer arrivals – especially when it comes to food and roots. Finding new ways and rediscovering traditional ways to maintain or reclaim your roots in a new environment and a new set of circumstances – whether imposed upon you painfully or a painful choice – is at the heart of food sovereignty. Carroll affirms, “I think you can tell a lot about a community by the way their food system is. Unfortunately, that identity aspect of it has been disrupted for a lot of our communities. I think a lot of our communities are trying to reclaim that”.

Danya’s work in tribal food sovereignty provides an example of community-based solutions that seek to reclaim and reaffirm identity through the central conduit that is relevant to all people: food. Don’t forget your food. Grow a garden. Connect your children and yourselves to the elders in your community by preparing and sharing a meal together. Know where you and your food come from.

About the Author

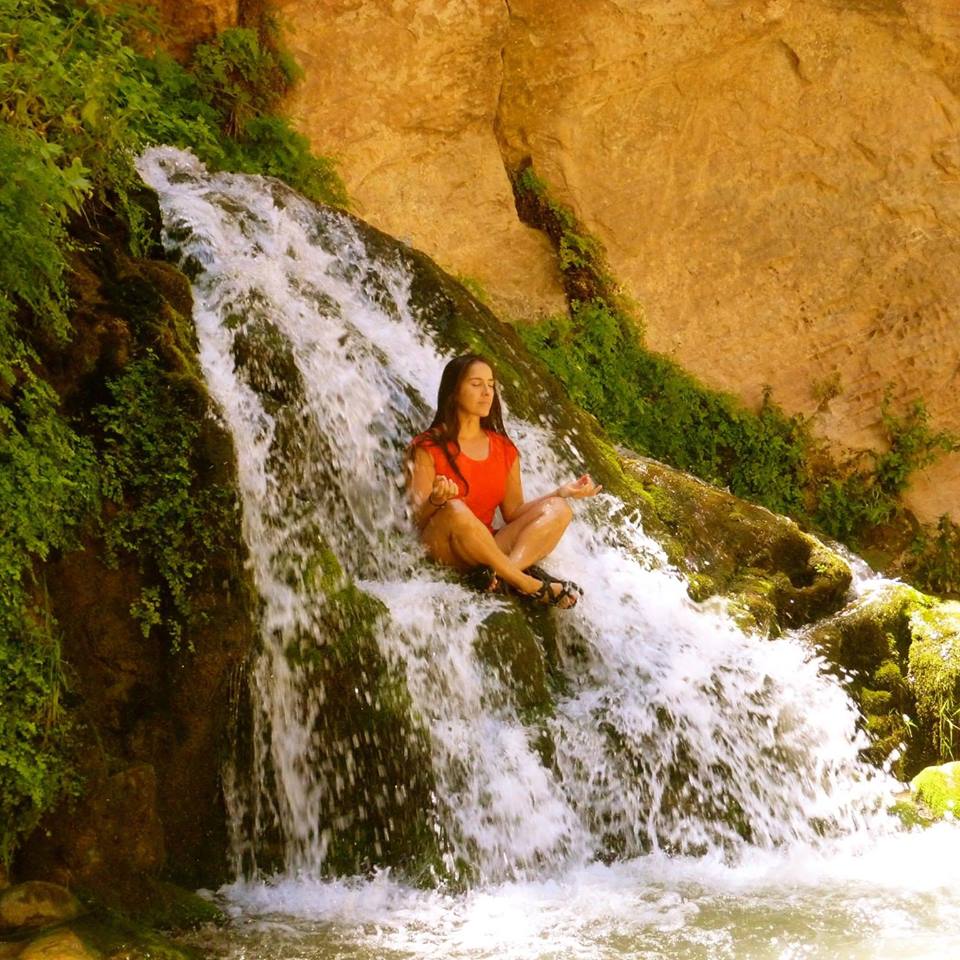

Rachael Novak, Dine’ or Navajo (Tse’ Deeshgizhnii, 1st clan, Kinyaa’aani, 3rd clan) is from the high desert country of the Intermountain West and currently resides in Washington, DC working on climate change adaptation issues in tribal communities. She has a garden in Washington of questionable success, but she keeps trying every year, inspired by friends and family near and far and of course of Mother Earth (Nahasdzaan Shima’).