The Gifts of a Recipe

“I have a recipe for you,” Grandpa announced. I was finishing up college, but it was Christmas break and I’d traveled with my father to his hometown in rural Arkansas. Grandpa waved a scrap of paper in the air encouragingly, so I opened my journal and copied it down:

Teacakes

1 cup sugar

1 cup shortening

1 or 2 eggs

1/3 teaspoon soda

2/3 teaspoon baking powder

4 tablespoons water

4 to 5 cups flour

Mix withhands. Roll out on floured board and cut with glass or cookie cutters. Bake at 400 degrees until crisp and slightly brown on some edges.The recipe was for the simple cut-out cookies once made by his maternal grandmother.

That December night I made my first batch. All we had for a rolling pin was an old wine bottle,  but it worked just fine. (How in the heck

but it worked just fine. (How in the heck

did my teetotaler grandparents get a wine bottle?) We made so many Teacakes that I ran out of plates to put them on. That night the small, 1950s-style kitchen was warm, fragrant, and the place I most wanted to be on Earth.

I monkeyed with the recipe some — committing to two eggs, adding a little almond extract, cutting back to just under four cups of flour. Now it worked better in a modern kitchen for modern palates. The recipe became a go-to and a holiday favorite. I learned fancy decorating with icing and soon was teaching this skill to family, friends, and strangers at charity events. Decorated Teacakes have crossed many thresholds as “Welcome to the Neighborhood” treats and traveled hundreds of miles in care packages.

A dozen years after the recipe came into my life, my parents and grandparents were gone. These early losses had nudged me into a career as an archivist. As I prepared to move to the city for a new job assignment, a friend handed me a battered black journal, part of the “1000 Journals Project.” An anonymous donor distributed a thousand blank journal books, inviting anyone interested to make an entry before passing it along. (A note inside asked whoever used the last page in a volume to return it so it could be scanned for a community website.) I only had Journal #258 for an evening, so I started writing in stream-of-consciousness fashion:

“In a few weeks I will pack up everything I own, move hundreds of miles, start over. Am I comparing moving van prices? Finding cardboard boxes? Reading apartment notices? Not yet. No. Right now I’m sorting and typing and indexing dessert recipes. Crazy? Perhaps. Procrastinating? Perhaps. But I read through ingredient lists and picture the uniform familiarity of eggs dropping into my old green mixing

bowl and the homey smell of cinnamon.”

Until I wrote the journal entry, I hadn’t realized my recipe collection was such a symbol of home. I added Great Great Grandmother Moseley’s recipe for Teacakes to Journal #258 before I passed it on.

The move turned out to be just what I needed. I bought my first house and had my own kitchen at last, painting it green and displaying vintage utensils from my grandparents’ kitchen. As a final touch, I scanned recipes in my grandparents’ handwriting to make collages for the walls. Many a batch of Teacakes were made in that kitchen and I finally lived close enough to my nieces and nephews that they could help.

My new job for the Georgia Archives involved helping teachers and students use primary sources in the classroom. I soon discovered, however, that if I asked classes, “Raise your hand if you like history!” only one or two hands would go up. If they don’t care about the past, how can young adults understand their lives in the greater context of community or make sense of modern day politics? After some mulling, I realized my love of history began with my grandparents, so that’s where I turned. I slipped family stories and show-and-tell artifacts into my presentations with very good results. The biggest hit was when I started baking Moseley Teacakes for classes. We talked about how different these cookies are from most modern cookies both in the way they taste and in how they once were made. The Teacakes were a springboard for discussions about yesteryear – old food customs and patterns of daily life, the sustenance farming economy, technological advances, and even topics such as gender roles and racial issues. I stopped having trouble getting the kids in the back to pay attention.

you like history!” only one or two hands would go up. If they don’t care about the past, how can young adults understand their lives in the greater context of community or make sense of modern day politics? After some mulling, I realized my love of history began with my grandparents, so that’s where I turned. I slipped family stories and show-and-tell artifacts into my presentations with very good results. The biggest hit was when I started baking Moseley Teacakes for classes. We talked about how different these cookies are from most modern cookies both in the way they taste and in how they once were made. The Teacakes were a springboard for discussions about yesteryear – old food customs and patterns of daily life, the sustenance farming economy, technological advances, and even topics such as gender roles and racial issues. I stopped having trouble getting the kids in the back to pay attention.

Inspired, I added information about preserving family recipes to my genealogy presentations for adults. Not long afterwards, I received an email from the University of Georgia Press asking if I’d like to write about the topic. More than two decades after the Teacake recipe came into my life, I used it in my first national book as an example of how to develop a recipe and learn more about family through foodways. With a nod to tradition and the gifts this recipe brought, my husband and I gave a copy along with a cookie cutter to everyone who attended our wedding. Our son arrived the following year and soon I could say that the recipe has brightened family gatherings for six generations.

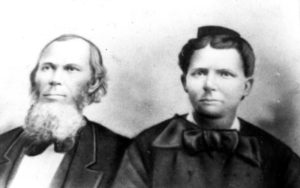

As I prepared to take to the author’s lecture circuit, I was confident that I’d learned all I could from the Teacake recipe. I’d explored the background of each ingredient and technique. I’d researched my genealogy and the history of southern women, revealing many facts about the life of the original cook, Ellen Moseley (1830-1900). The last detail  I needed was a photograph of her grave. I made a trip to visit cousins still in the area and one frosty November morning we wound our way down a dirt road covered in autumn leaves to get to the small family plot. The cemetery that had once been a space between fields had grown into a grassy hollow surrounded by deep woods. I found the worn, mildewed stone and snapped a few photos. Then I pulled out a county cemetery guide to verify the tombstone dates. It was then that I noticed a paragraph at the top of the page. The guide explained that Ellen and her husband, Mason, started the cemetery when their infant son died in 1862. The guide also noted that during the Civil War the family claimed the body of an unknown U.S. soldier, most likely gone astray from the nearby Battle of Marks Mill, and buried him there.

I needed was a photograph of her grave. I made a trip to visit cousins still in the area and one frosty November morning we wound our way down a dirt road covered in autumn leaves to get to the small family plot. The cemetery that had once been a space between fields had grown into a grassy hollow surrounded by deep woods. I found the worn, mildewed stone and snapped a few photos. Then I pulled out a county cemetery guide to verify the tombstone dates. It was then that I noticed a paragraph at the top of the page. The guide explained that Ellen and her husband, Mason, started the cemetery when their infant son died in 1862. The guide also noted that during the Civil War the family claimed the body of an unknown U.S. soldier, most likely gone astray from the nearby Battle of Marks Mill, and buried him there.

It is now a quarter of a century that I’ve had the Teacake recipe and I no longer presume that it has given all of its gifts. Right now our nation is deeply divided politically. Like many, I feel caught between upholding my core beliefs and respecting the beliefs others hold dear. But the recipe points me back to a time when our nation was divided to a much larger degree. I think about Ellen and wonder if giving a stranger, one of the “enemy,” a resting place next to her lost child was a difficult decision. I wonder if in a time when tempers were high and the war had come to their doorstep if she had to defend that decision to her neighbors. I will likely never know. But I do know that following the trail of a family recipe brought me the story of a long-ago kindness that over a century and a half later deeply inspires the great great granddaughter Ellen never got to meet.

Now I can only wonder – what will this recipe’s next gift be?

About the Author

Valerie J. Frey is a writer and archivist. Her projects focus on personal writing, storytelling, genealogy, local history, material culture, folklife, and home life both modern and historic. Valerie’s most recent book, Preserving Family Recipes: How to Save and Celebrate Your Food Traditions published by University of Georgia Press, is a guide for gathering, adjusting, supplementing, and safely preserving family recipes and for interviewing relatives, collecting oral histories, and conducting kitchen visits to document family food traditions from the everyday to special occasions.

Follow Valerie’s work at:

Facebook: 150069945339292

Instagram:@ValerieJFrey

Twitter: @ValerieJFrey